THE STONEHENGE

RAMPAGE

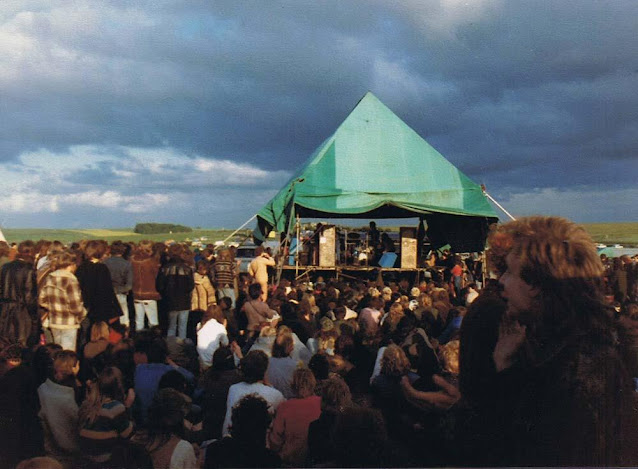

That summer of 1980,

in an entirely different corner of society another smaller yet far

more grievous riot of sorts took place, this time out on the

Wiltshire plains at the annual Stonehenge Free Festival.

Unbeknownst to their

burgeoning audience at that time, members of Crass had been seminal

to the setting up of the first Stonehenge festival in 1974. From it

beginning as a gathering of a few hundred hippies in those early

days, it had steadily grown and developed into an absolutely unique

cultural phenomenon that by 1980 was attracting thousands. The

Stonehenge festival was an example of freedom in the raw where

practically anything was allowed due to the total lack of police

presence. Standing like a post-apocalyptic shanty town where the

music was free (courtesy of Hawkwind et al), the food was cheap or

even free (courtesy of the Hari Krishnas), and the drugs were in

abundance; it was a glimpse into how anarchy might - or might not -

work.

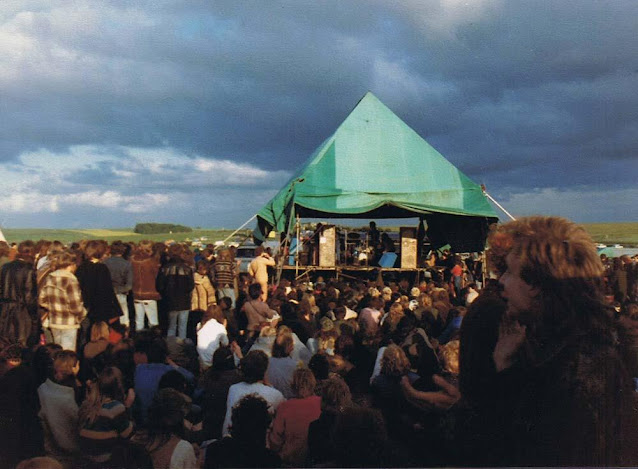

Crass had played at

the festival the previous year but on returning that following

summer, due to their rising popularity they had attracted a large

number of Punk Rockers to the site. Though Punk had moved on somewhat

from the days of Sex Pistols-type outrage, to some, Punk still

represented a challenge that was difficult to come to grips with.

Teddy Boys, of course, were famously known for their dislike of Punk

but unexpectedly there seemed to be certain bikers who also shared

that disdain.

From its outset,

Stonehenge was a predominantly hippy affair but as it grew so did the

composition of its attendees, pulling in all kinds of people from

different sections of society including straight-dressed kids from

council estates (taking full advantage of the drugs sold openly

there) and chapters of bikers (taking full advantage of the drugs

also, of course). The council estate kids were fine and treated the

festival like a narco Butlins so were simply there for a good time

(and all the rest was propaganda) but a lot of the bikers seemed to

have something to prove. Arriving on site usually in convoys, they

would park up in circles and claim areas of the site as their own.

Which was fine - anything that made them happy. Some, however, would

claim the whole festival as their own and it was these who didn't

take too kindly to what they saw that year as a Punk invasion.

Throwing bottles at

Punk band The Epileptics was the first sign of their displeasure,

which then quickly escalated to them seeking out and attacking any

Punk Rocker they could find. The ensuing violence was brutal and

frightening.

'Bikers Riot at

Stonehenge' read the headline in the following week's NME though in

truth it was more of a mindless rampage. The incident, however,

convinced Crass to decide never to play Stonehenge or any other free

festival again, which was really unfortunate. Nevertheless, by Crass

being there at all a chain reaction had started and the floodgates

were now opened. The budding Anarcho Punk culture had met

face-to-face with free festival culture - causing a mutation in both.

The year 1976 and

the advent of Punk is often cited as Year Zero. For some, this is

undoubtedly the case but at the same time, Punk - and in particular

the Sex Pistols - opened up the past and shone a light upon a

veritable treasure trove of reference points and influences: The New

York Dolls, Iggy Pop, the Velvet Underground, Patti Smith, the MC5,

Captain Beefheart, Dr Feelgood, The Doors, The Who, Alice Cooper, the

Situationists, King Mob, nihilism, anarchy, the mythology of the

Berlin Wall and the Chelsea Hotel, Paris '68, Dickensian London,

amphetamines... and heroin.

Likewise, Crass also

illuminated a plethora of references, ideas, influences and

possibilities; many intentionally but others not so: John Lennon,

Walt Whitman, RD Laing, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Sartre, Arthur

Rimbaud, Baudellaire, George Orwell, Richard Hamilton, John

Heartfield, Wilfred Owen, anarchism, pacifism, feminism, atheism,

existentialism, pop art, collage, Dada, graffiti, CND, black clothes,

squatting, free festivals, hashish... and LSD.

All links in a

chain. All important stepping stones to an ultimate yet unknown

destination.

Worlds were

colliding - be they political, social or cultural - causing

metamorphosis, unification, friction and (as at Stonehenge) sometimes

outright conflict.

It was the dawn of a

new decade and as events unfurled in St Paul's in Bristol and at the

Stonehenge Free Festival, less significantly (or perhaps more so?)

the music charts were being assailed by such classic bands as The

Jam, Dexy's Midnight Runners, and The Specials. It was Crass,

however, who were arguably becoming the most important band in

Britain due not only to their own records but also to the records

they were releasing by other artists on their label...